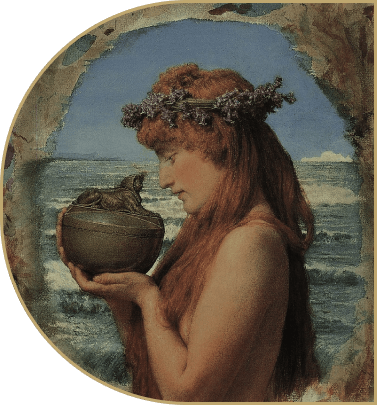

Pandora's box is an artifact in Greek mythology connected with the myth of Pandora in Hesiod's c. 700 B.C. poem Works and Days.

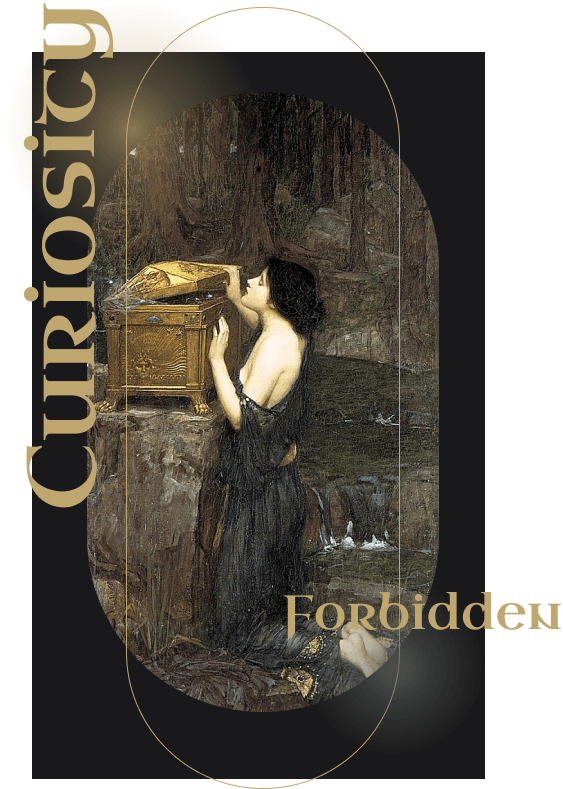

Hesiod related that curiosity led her to open a container left in the care of her husband, thus releasing curses upon mankind. Later depictions of the story have been varied, with some literary and artistic treatments focusing more on the contents than on Pandora herself.

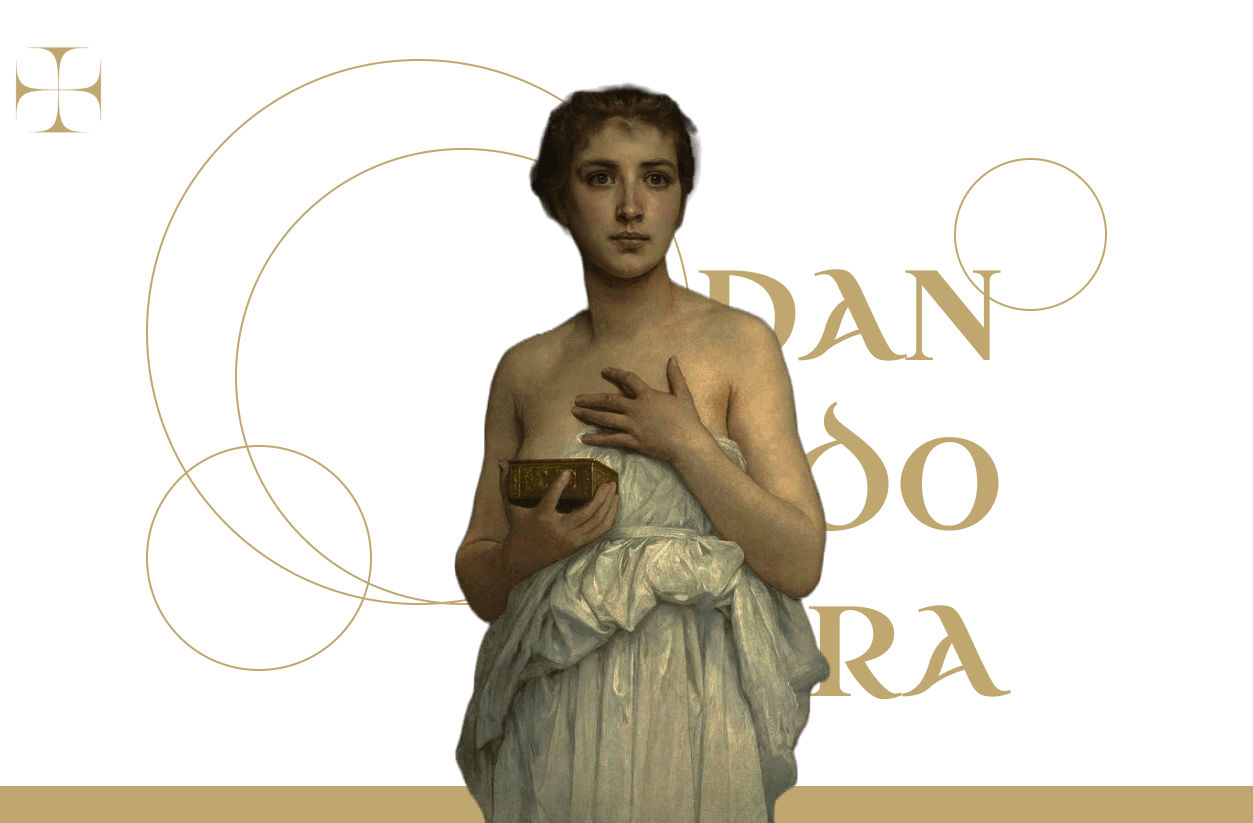

In Greek mythology, Pandora (Greek: Πανδώρα, derived from πᾶν, pān, i.e. "all" and δῶρον, dōron, i.e. "gift", thus "the all-endowed", "all-gifted" or "all-giving") was the first human woman created by Hephaestus on the instructions of Zeus. As Hesiod related it, each god cooperated by giving her unique gifts. Her other name—inscribed against her figure on a white-ground kylix in the British Museum—is Anesidora (Ancient Greek: Ἀνησιδώρα), "she who sends up gifts" (up implying "from below" within the earth).

The meaning of Pandora's name, according to the myth provided in Works and Days, is "all-gifted". However, according to others, Pandora more properly means "all-giving".

Certain vase paintings dated to the 5th century BC likewise indicate that the pre-Hesiodic myth of the goddess Pandora endured for centuries after the time of Hesiod. An alternative name for Pandora attested on a white-ground kylix (ca. 460 BC) is Anesidora, which similarly means "she who sends up gifts."

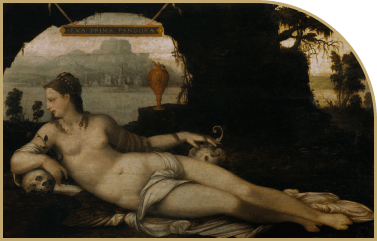

The Pandora myth is a kind of theodicy, addressing the question of why there is evil in the world, according to which, Pandora opened a jar (pithos) (commonly referred to as "Pandora's box") releasing all the evils of humanity. It has been argued that Hesiod's interpretation of Pandora's story went on to influence both Jewish and Christian theology and so perpetuated her bad reputation into the Renaissance. Later poets, dramatists, painters and sculptors made her their subject.

Hesiod, both in his Theogony (briefly, without naming Pandora outright, line 570) and in Works and Days, gives the earliest version of the Pandora story.

The Pandora myth first appeared in lines 560–612 of Hesiod's poem in epic meter, the Theogony (c. 8th–7th centuries BC), without ever giving the woman a name.

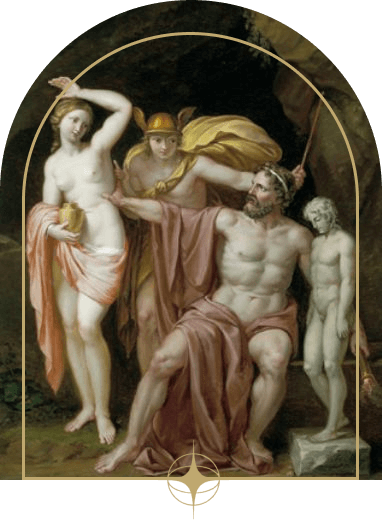

After humans received the stolen gift of fire from Prometheus, an angry Zeus decides to give humanity a punishing gift to compensate for the boon they had been given. He commands Hephaestus to mold from earth the first woman, a "beautiful evil" whose descendants would torment the human race. After Hephaestus does so, Athena dresses her in a silvery gown, an embroidered veil, garlands and an ornate crown of silver. This woman goes unnamed in the Theogony, but is presumably Pandora, whose myth Hesiod revisited in Works and Days. When she first appears before gods and mortals, "wonder seized them" as they looked upon her. But she was "sheer guile, not to be withstood by men."

According to Hesiod, when Prometheus stole fire from heaven, Zeus, the king of the gods, took vengeance by presenting Pandora to Prometheus' brother Epimetheus.

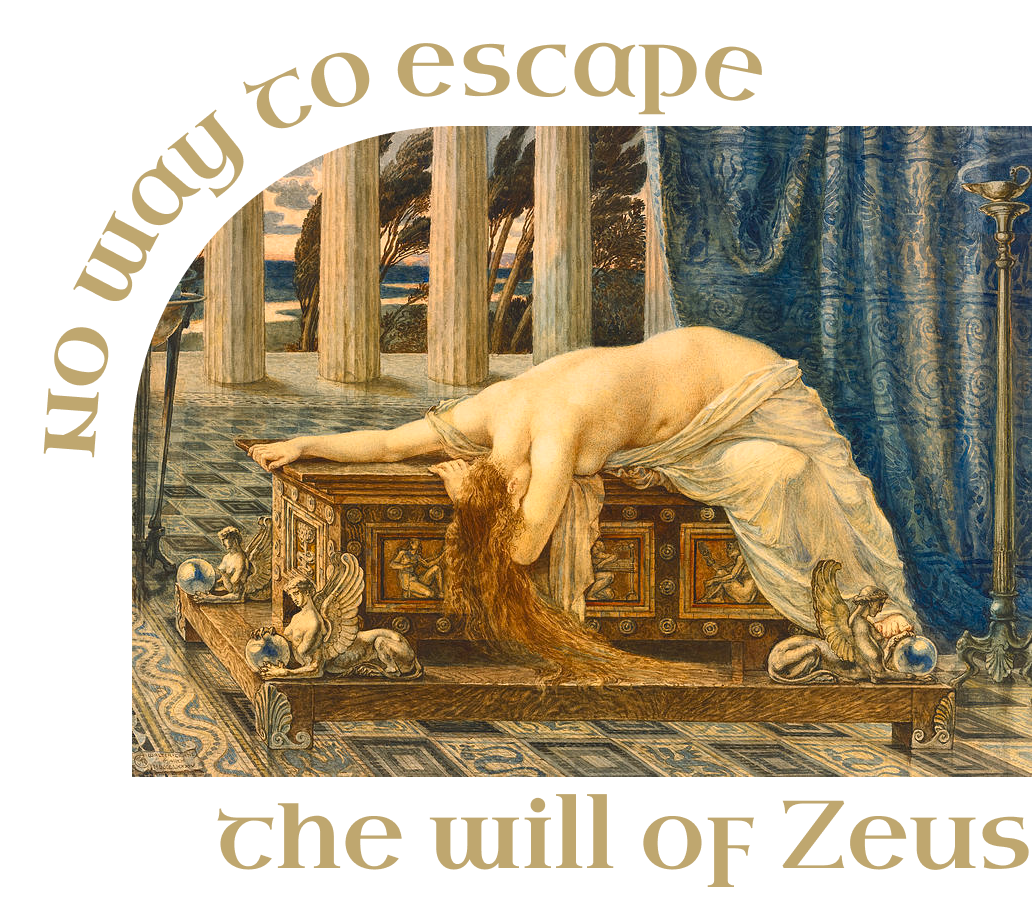

Pandora opened a jar left in her care containing sickness, death and many other unspecified evils which were then released into the world. Though she hastened to close the container, only one thing was left behind – usually translated as Hope.

Only Hope remained there in an unbreakable home within under the rim of the great jar, and did not fly out at the door; for ere that, the lid of the jar stopped her, by the will of Aegis-holding Zeus who gathers the clouds.

The more famous version of the Pandora myth comes from another of Hesiod's poems, Works and Days. In this version of the myth (lines 60–105), Hesiod expands upon her origin and moreover widens the scope of the misery she inflicts on humanity.

As before, she is created by Hephaestus, but now more gods contribute to her completion: Athena taught her needlework and weaving; Aphrodite "shed grace upon her head and cruel longing and cares that weary the limbs"; Hermes gave her "a shameless mind and a deceitful nature"; Hermes also gave her the power of speech, putting in her "lies and crafty words"; Athena then clothed her; next Persuasion and the Charites adorned her with necklaces and other finery; the Horae adorned her with a garland crown. Finally, Hermes gives this woman a name: "Pandora [i.e. "All-Gift"], because all they who dwelt on Olympus gave each a gift, a plague to men who eat bread".

In this retelling of her story, Pandora's deceitful feminine nature becomes the least of humanity's worries. For she brings with her a jar (which, due to textual corruption in the sixteenth century, came to be called a box) containing "countless plagues". Prometheus had (fearing further reprisals) warned his brother Epimetheus not to accept any gifts from Zeus. But Epimetheus did not listen; he accepted Pandora, who promptly scattered the contents of her jar. As a result, Hesiod tells us, the earth and sea are "full of evils". One item, however, did not escape the jar:

Only Hope remained there in an unbreakable home within under the rim of the great jar, and did not fly out at the door; for ere that, the lid of the jar stopped her, by the will of Aegis-holding Zeus who gathers the clouds.

Hesiod does not say why hope (elpis) remained in the jar. Hesiod closes with a moral: there is "no way to escape the will of Zeus."

Hesiod also outlines how the end of man's Golden Age (an all-male society of immortals who were reverent to the gods, worked hard, and ate from abundant groves of fruit) was brought on by Prometheus. When he stole Fire from Mt. Olympus and gave it to mortal man, Zeus punished the technologically advanced society by creating a woman. Thus, Pandora was created and given the jar (mistranslated as 'box') which releases all evils upon man.

From this story has grown the idiom "to open a Pandora's box", meaning to do or start something that will cause many unforeseen problems. A modern, more colloquial equivalent is "to open a can of worms".